The small class included Timothy Bavin and Robert Alexander, and intellects like theirs needed little extra instruction. For their essays on Roman History I used titles I had been set four years previously and, more importantly, the notes I had taken down when my Greats tutor had tried to remedy some of the inadequacies in my own efforts.

For the most intellectually distinguished on the Arts side during my time at the College I would add to those two names above, Richard Buxton and Robert Skidelsky. The former wrote a play about Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus which Peter Gough produced and directed, insisting on programme notes in Latin. The latter stayed on for a year after his A Levels and came to me at the end of the Easter Term to enquire about the Ancient History syllabus. I saw no more of him but found out four months later he had achieved an A grade on his own initiative. No wonder his subsequent academic career prospered, although I do remember he came back to give a lecture in the year of the OPEC crisis and predicted that we would soon be growing potatoes in the Front Quad in order to survive!

Jack Head the Bursar had been at school with my father but I hope that was not the only reason Bill Stewart gave me the job. ‘Tickety-Boo’ as he was always known ran the whole administration with his hyper-efficient secretary, Miss Ball, from the room now occupied by the Deputy Headmaster – some contrast with the present management staff who have expanded to cope with the phenomenal increase in numbers, premises and facilities and now occupy the entire ground floor of the Dawson Building, the rooms of which make much better offices than classrooms. Commander Head had run HMS King Alfred, the wartime training establishment for RNVR officers in Hove, and one of his many services to the College was to bring in ex-CPOs with all their loyalty and reliability to man different departments like maintenance and workshops. Then on Fridays they would put on their old uniforms and train the Naval Section of the CCF.

In the Common Room T A Hill and R L Farnell had served in the First World War and Martin Jones records how in the Second they had “done yeoman service with a cheerful readiness to do anything at any time by day or night.” Archibald Hill suffered badly from arthritis – he had won a sprinting blue at Oxford – and taught all his classes from the depths of a large armchair. I thought the greatly respected Ralph Farnell an intimidating figure at first but he was always ready to help a young colleague. Once when I was drafted in to teach a bottom English set he was amazed to be asked whether he invariably counted the number of words in a précis – a weekly exercise. It had obviously never occurred to him to trust a schoolboy’s computation.

Tom Smart had been RLF’s batman in the trenches and the school would not have functioned without him, although he still suffered the effects of being gassed. On top of his other multifarious duties as Porter he was responsible for all the coal fires in the Main Block, and mine in Room C (now the Library) burnt a hundredweight a day, which had to be carried up from the cellar. When warmth was permitted late in the winter term old lags who had previously sat in the rear row would rush to be first in to ensure a place near the fire. The smell of charring wood surprised us one day as a red hot poker appeared through the panelled door from the cerebral haunt of Higher Mathematics.

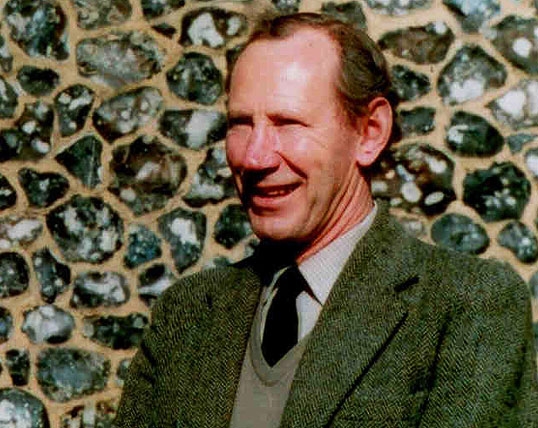

That generation knew nothing about B. Ed or PGCE but for me the most striking transformation brought by a professional approach took place on the rugger field. Geoffrey Lees had established a winning tradition in cricket that has been well maintained by John Spencer. In fact GWL was the character I have most admired in my whole career and no one else possessed the same alchemic gift of bringing success to all he touched: cricket and squash, English Department and Aldrich House, and later as Headmaster of St Bees.

By contrast Bernard Boddy, though a wonderful athlete and centre-half for Pegasus, was not a triumphant rugby coach and in the 50s we watched the XV experience more defeats than victories. The nadir of humiliation came at an away match at Cranleigh with a report in the Guardian next day when their rugby correspondent said a Brighton forward told him he had never played on the winning side at any level.

Anyway John Pope was an inspired choice by Henry Christie and I saw him in action at close quarters. He used to disappear on Saturdays to play for Rosslyn Park and gave me the privilege of escorting the XV and carrying the First Aid bag – one wet sponge! On practice afternoons he would appear on the Home Ground with his lesson plan neatly written out and proceed to give a master class to 30 boys instilling individual and team skills. It still took him nearly ten years before every match was won and Old Brightonians no longer had to look back to the 20s for days of glory. Of course before the switch to rugby in 1919 Brighton had won the Public Schools Challenge Cup in 1910 and the Arthur Dunn Cup for old boys sides in 1913.

Current academic achievements show the difference professionally trained teachers make in the classroom – in the decade of the 20s a total of 26 pupils gained Higher Certificates and in the period 1940 -45 only 38 passed. So nobody should lament that the era of amateur schoolmasters has passed, although many of us preferred that term on our passports in order to avoid any hint of a link with the NUT. Unfortunately I did not read Jonathan Smith’s The Learning Game until I retired and learnt he had been rebuked by his parents for avoiding the job description ‘teacher’. (See John III.2!) His book should be a prescribed text for paedagogues and I can also recommend his Wilfred and Eileen, dedicated to Marjory Seldon, which is an imaginative reconstruction of the life of Dr Seldon’s grandfather, nearly killed by a skull wound in 1914.

Richard Holme’s last book Tommy, a ‘landmark’ volume on WW1, mentions Peter Chasseaud as “the doyen of the war’s topographical historians” and says no serious student of the First World War should be without his Topography of Armageddon. Peter was a colleague in the 80s and supplied the provenance of some trench maps and a panorama of the Ypres Salient I had found among my father’s papers. I never knew until now that such a definitive opus was in gestation.

Richard Holmes also warned against the dangers of oral history and any of us who have read subsequent accounts of events we actually witnessed know what distortions and varied interpretations occur. So if anyone who has read this far can add to or correct these reminiscences I shall be grateful.

David Gosling (S. 1954-59) writes in response to John Page's 'Jubilee' in the recent Pelican:

By a means I cannot now account for, I won the Latin Prize at the College for (I think) all my years there. So, I was one of the fortunate ones to have lessons from John Page in that lovely room above the Porter's Lodge with its splendid Oriel windows. I can only add one particular reminiscence, which concerns the magnificent coal fire. The fire surrounds were (as I recall) made of lead and the poker, when suitably heated, was used to create holes in the lead surround, and of course to make a great deal of smoke - all before John Page appeared in the room, of course.

On other topics raised in the article:-

T A Hill - aka 'Blimp' regaled us often with tales of seeing the first tank in action in the Great War. The story (as others) prefaced with the words "I was there".

There was an unofficial school song which amongst others included the references to - "Smart, Smart the 'Allo Boy, clothed all in green, Oh Oh" as part of the chorus and "Spits" (Mr Farnell) "has apoplexy" as one of the lines parodying the staff, all of which now forgotten. All sung to the tune of "Green grow the rushes Oh" and all to be learnt by heart as part of an initiation test imposed on new boys in School House by slightly less new boys.